Resisting a Singular Narrative

March 3, 2017

by Hannah Brancato

As the co-founder of FORCE: Upsetting Rape Culture, I’ve had many big picture conversations with friends and family since the recent presidential election about what resistance can and should look like during the Trump presidency. I’ve been reminded of how hard it is for people to look past their own situations and how pressing it is to see our struggles as connected. I am a white woman and I’ve found that the conversation begins with gender. I always try to bring up the fact that we can’t talk about gender or gender-based violence without talking about race, ability, and sexual orientation. A lot of times, this idea is met with confusion, anger and resistance by other white women. In turn, I often become frustrated, angry, even confused. I’ve been reflecting a lot on how to be effective and compassionate in communicating the urgency of intersectionality, especially to other white women. So much is at stake and at the same time people don’t know what they don’t know. I want to walk beside people as they learn, as other people did (and do) for me. In that context, I want to share about a project that I am a part of, how I show up in it as a white women, and the ways in which it manifests the idea of intersectionality. What follows is credited to all of the indigenous people and people of color who have educated me and influenced my understanding of intersectionality.

March 1, 2016

Mary Anna Pomonis

Two years ago I received an exciting email from a curator at an art museum. I was solicited to participate in an international exhibition. This is an excerpt from the emailed I received:

“Each of us finds our ethical position slowly through a combination of family values, community norms and cultural signifiers.These influences bring together sets of potential positions for us to sift through and begin the process of decision making that leads us to adulthood. The sources for much of these influences can be varied and of varying quality but we seem to make out OK in the end, or at least most of us do."

Voices of Change: Part 1

March 1, 2016

CBA Prison Arts Collective (Teaching Artists)

Prologue

In 2011, as part of a new Service Learning class, I supported students in facilitating weekly art classes at two local sites with limited access to art; in just three years, this has evolved into the collective initiative, Community-based Art (CBA), in which dozens of students, alumni, and volunteers facilitate regular art

March 1, 2016

CBA Prison Arts Collective (Participating Artists)

Open Letter about Art in Prison

To whom it may concern:

As an inmate who has served 28 years and struggled with addictions, anger problems, and criminal thinking, I want to share with you how art has changed my life.

March 1, 2016

Pamela Lawton

My interests as an artist, educator, and researcher converge around the concept of community, in particular intergenerational art making and the learning that takes place through informal educational structures. In this way, I have developed several courses (Art Education and Social Justice, Art and Lifelong Learning, Community Based Teaching and Learning, Studio Based Teaching and Learning) that provide me with an opportunity to introduce college students to the idea of art making with learners across the lifespan in a collaborative, community setting. The learning that takes place in these communal collaborations is often transformational. Transformation can occur on both the personal and communal level.

March 1, 2016

Rachel Mason

I recently learned about a new art project by the British artist, Phil Collins (no relation to the singer) about Sing Sing Prison. Hearing about this film-in-progress reminded me of my own experience as a volunteer at Sing Sing Prison and a project I had planned to make about my time there. It also reminded me of the reasons that I never carried out that project.

March 1, 2016

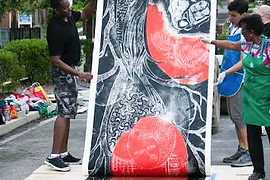

Michael Carriere and Nicolas Lampert and Paul Kjelland

For much of the twentieth century, Milwaukee was the self-proclaimed “Machine Shop of the World,” a place where industrial opportunities provided the means for a variety of newcomers to carve out a stable home in the city. At its peak, Milwaukee was the second densest city in the United States — just behind New York — with real estate values that reflected such a reality. In response to these developments, the city undertook a massive annexation program, looking to purchase surrounding

communities in an attempt to give the city and its residents some room to grow.

March 1, 2016

Ray Smith

Corita Kent (1918-1986) was an artist, educator, and advocate for social justice who worked primarily in serigraphy. She began her teaching career as Sister Mary Corita at Immaculate Heart College (IHC) in Los Angeles in the mid-1940s. The religious order she was a member of, the Immaculate Heart of Mary (IHM), was a teaching order and upon completion of her education, Corita was sent to a primary school in British Columbia. Corita was known in the order as being artistic and, when the college was seeking accreditation, it was suggested they call her back to add to the faculty. At that time, Sr. Magdalen Mary was the only art professor and at least two were necessary to be an accredited art program.